Content note: Spiders. 🕷️🕷️🕷️. Discussion of the book Children of Time by Adrian Tchaikovksy, but contains no major spoilers.

I recently read the book Children of Time, and I thought it was really great sci-fi. It has good world-building and good characters. One of the protagonists is a spider. I recommend it! In fact many of the characters are spiders, and the book contains a first-contact sort of scenario, where humans and spiders have to learn to communicate with each other.

This got me thinking, what sort of language would spiders use, if they independently evolved language?

In the book, they are “uplifted” animals, which in this case means that they gained greater intelligence through guided evolution. But they’re essentially spiders (from Earth); they aren’t augmented with a cybernetic interface, and they weren’t pushed to be more mammalian, just smarter. So I think their language should be very spider-like, and it might be quite different from human languages.

The book does talk about what their language is like, but it mostly talks about how they relate to it physically. It’s based on vibrations which the spiders feel through their feet, which is similar to how spiders detect the movement of insects or detritus in their web. The spiders in the book are of the genus Portia, which invade the nests of other spiders, so in real life they’re quite smart, and they pay great attention to the vibrations caused by other spiders on the web, which they intend to prey upon. In fact, they can even make stereotyped vibrations that mimic a specific insect caught in the web. So that gives us some idea about the phonetics of the language.

But what’s the syntax like? I think their syntax might be web-like in a different way.

What is Syntax?

This is a bit of a digression about human syntax, because I think it’s important to understand how grammar allows us humans to convey information.

Language, of any sort, faces the problem that the map is not the territory on two levels. First, the speaker builds up a mental map of the world around them in their mind, and then they need to finagle their mental map into words in order to communicate it.

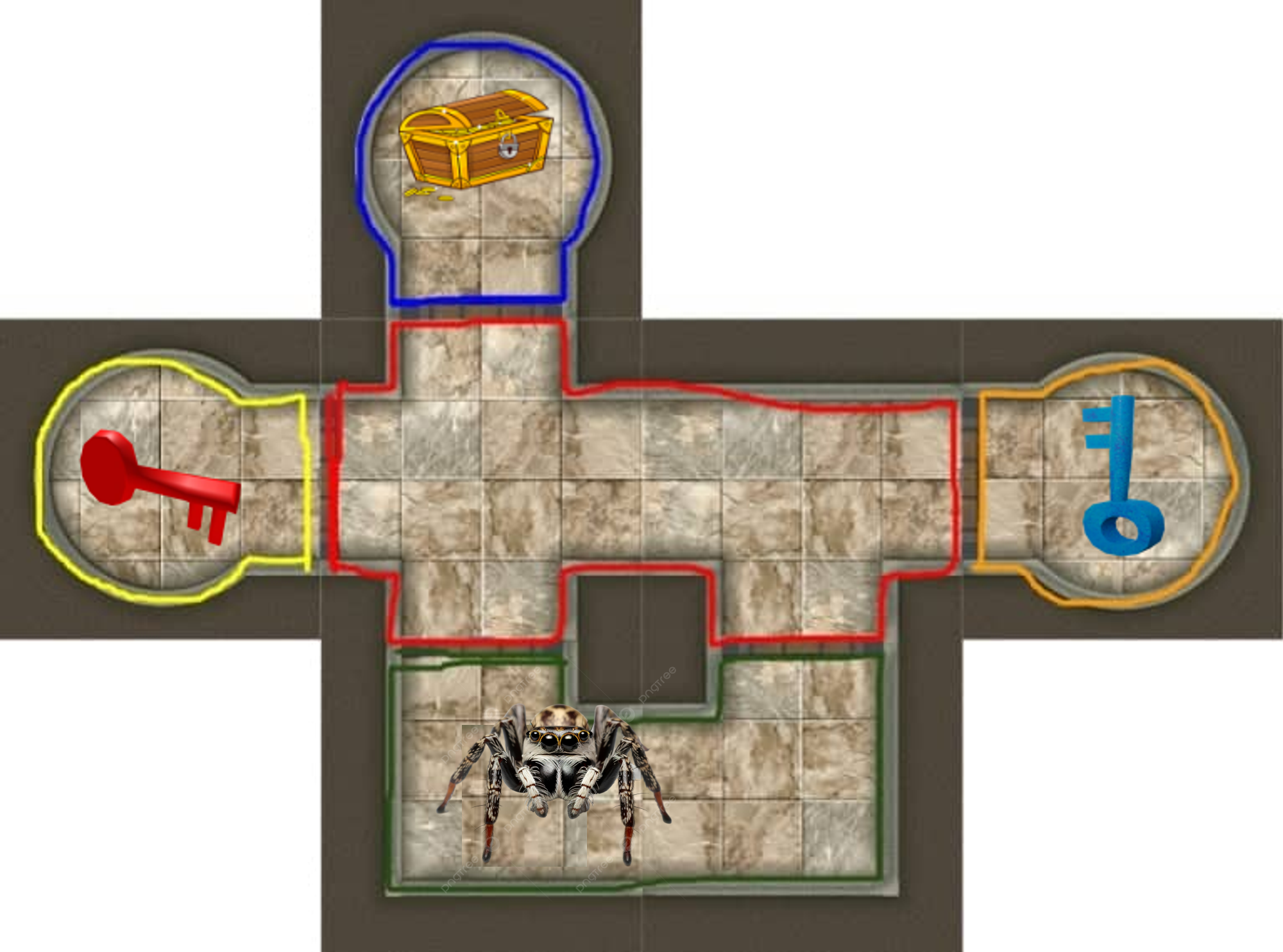

Let’s look at a concrete example of a territory:

Here our explorer has already explored the rooms around her, and has built up a mental map of what’s there. It’s difficult to say exactly what the nature of her understanding of the world is like; there’s unfortunately not a clear answer from cognitive neuroscience about how beliefs are represented.

However, one useful model is that neurons in the human mind are arranged in a sort of graph, a “neural network” if you will, and so we can say that our knowledge is arranged in some sort of graph structure. In computer science, there’s the idea of a knowledge graph as a way of representing structured data; you’ve almost certainly interacted with Google’s knowledge graph when you look things up online. So we can think of human understanding as being graph-like, even if that’s an oversimplification.

Anyway, here’s one representation of some information that our explorer knows about the world:

Now, the explorer wants to convey something about the world. What she is going to say is:

“The blue key for the blue room is in the yellow room”

Human language, and this is true of basically all languages, from Basque to Bantu to Nicaraguan Sign Language, is based on a tree-like grammatical structure. That basically means that we can expand on any phrase, and then expand on subphrases within it, using something like a context free grammar. So “I saw a [bird]” can become “I saw a [bright green bird]” and so on. This isn’t strictly true in all cases, but it’s a good model 99% of the time.

Let’s look at what’s going on in our explorer’s mind. I’ve removed the word “the” for clarity.

S=Sentence, NP=Noun Phrase, VP=Verb Phrase, PP=Prepositional Phrase

When we speak, we emit words one at a time, in a sequence. But in our minds as speakers and as listeners, we arrange them into a tree structure like this.

This paragraph is speculation: Evolutionarily, humans developed the ability to understand language as a generalization of our ability to understand sounds. First, we learned to recognize sounds, like the call of a badger, or the distinctive rustling of a nesting bird, and we generalized that into understanding arbitrary words. Once we had the machinery to recognize words as a stereotyped series of sounds, we then developed the ability to recognize phrases as stereotyped sequences of words, allowing us to build up trees as a listener.

Because trees are a subset of graphs, human speakers can use tree shaped language to convey information about our internal knowledge graph. We can’t communicate the entire graph structure at once, but we can express bits and pieces of it, one sentence at a time.

Here is how our explorer’s sentence is mapped onto her knowledge of the world:

When another person hears those words, they parse them grammatically to get a syntax tree, then they build up a semantic tree of information, and then they assimilate that semantic tree into their internal knowledge graph.

But back to spiders. Spiders already have a built-in way of working with graphs. They spin webs!

Interlude: Spider Evolution

The spiders in the book Children of Time are jumping spiders of the genus Portia. Most jumping spiders do not usually spin webs. This presents our problem for our theory that these spiders might have developed a web-based language.

But! Jumping spiders do produce silk, which they use for abseiling down, for wrapping up their prey, and sometimes actually to spin webs. Just, not the classical kind of spider web that you’re probably thinking of.

It made me wonder, did the ancestors of jumping spiders spin webs? If so, they might have some genetic memory of it.

Jumping spiders, like the common wolf spider, are in the “RTA clade”, which produces “substrate defined webs”, meaning that their webs are heavily influenced by their surroundings, unlike a classic orb web, which looks very similar in any surroundings.

Well, they do spin webs of some sort. Between that and their instincts for using silk to make nests and to wrap their prey, I’m going to go ahead and continue speculating about what their web-based language might be like. I think it’s an idea that might make more sense for an orb web spinning spider like the yellow garden spider than for Portia spiders, but jumping spiders do have some web-spinning instincts.

How do Spiders Make Webs?

How do spiders actually make spider webs? What’s the sequencing like of the threads that they put down to build up a web? I found this amazing paper that talks about it

This paper put spiders under cameras and carefully recorded their positions as they spun their webs. Science is cool sometimes. Here’s how they describe what they found:

The spider goes through these steps:

- It spins a proto-web, which is messy and chaotic, but anchors the web in place

- It spins radial webs, spokes that meet in the middle

- It spins auxiliary and capture spirals around the center

- Then they make stabilimentum, which I think adjust the tension of the web

Syntax Webs

So! Let’s recap! Spiders spin webs. Jumping spiders like the Portia in the book spin webs, but not fancy ones. Spider webs kind of look like graphs. Knowledge of the world kind of looks like a graph.

Now what if the syntax for spider language was based on their instincts for spinning webs? Would that work? What would it look like?

Based on what we know about how spiders spin webs, I’m going to suggest that their language might be structured in the same way. Except that instead of spinning web, they would speak words, like the characteristic vibrations that Portia uses to fool a spider on whose web she’s trespassing.

When spiders make their webs, they first make radial spokes, and then they make a spiral around those spokes. Let’s imagine that their language is structured the same way.

Let’s put another explorer in our world. This time she’s a spider:

The human explorer said “the blue key for the blue room is in the yellow room”. How could a spider convey the same thing? The spider explorer wants to communicate about the blue key, so let’s put that at the center of her language web. We said that their language might be based on radials and then a spiral. What would the radials be? Let’s imagine that she wants to communicate what the key is, what it’s for, and what place it’s in.

- Is: Blue, Key

- For: Blue, Room

- In: Yellow, Room

A spider speaker could speak words for the radials first, like how they come first in the web, and then speak the words for characteristics of the radials in a spiral around them, requiring the listener to do a modulo operation as they go.

So the sequence might be:

Radial-Start, Is, For, In, Spirals-Start, Blue, Blue, Yellow, Key, Room, Room

A spider could listen to that sequence and, following along with the steps for making a web, reconstruct a mental graph that contains the intended structure. The idea of the blue key is wrapped up like prey in the center of this web. The listener could take this segment of the speaker’s knowledge graph, and incorporate it into their own, allowing knowledge transfer to take place. And what is language? It is a protocol, a system of rules, to facilitate the transfer of knowledge.

If spiders communicated with this sort of syntax, their language would be fully general to the same extent that human language is. Both human tree-syntax and spider web-syntax would allow speakers to extract snippets of their knowledge graph and communicate them. The rules of grammar in both cases would allow the listener to reconstruct the structure that the speaker had in mind, and because that structure is graph shaped, the listener could incorporate it into their own mental knowledge graph of the world.

But this syntax isn’t fully equivalent to human syntax. Humans are able to express a tree of content within a sentence, and this proposed grammar doesn’t have the same expressivity. Instead, this web grammar would allow speakers to communicate a group of one concept per radial, with a group of descriptors for each concept. That isn’t the same as transmitting semantic trees, but it’s enough to be fully general with respect to combinatoric semantics.

In the book, the humans struggle at first to parse the spiders’ language. Perhaps because it was structured so differently than they expected. If you liked this review, consider reading the book. The second book in the trilogy is about octopuses; if people like this article, I think octopus language might be even more different.

Comments

2 responses to “⭐ Review: Children of Time and the abstract purpose of grammar”

For the spiral, for the spider, if the spiral is a representation of syntax, can you clarify what objects would mean? As in the the third arch might be the second for, but what would differentiate a blue key from a red key at that point.

I was imagining that each radial of the web would be like one phrase, without allowing subphrases. So an object might be represented by a radial on the web, with adjectives describing that object as words presented in sequence for that object.